Good morning fellow ECAHF’ers. America was already at war with the Empire of Japan and it took four months to plan and execute the Pearl Harbor “revenge attack”, an audacious, risky, and uniquely American “suicide mission” requiring only volunteers (of which there were none lacking), all of whom wanted to—and believed, as most young people do who believe they are invulnerable, they would—come back to their loved ones. On April 18, 1942, according to History.com, “16 American B-25 bombers, launched from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet 650 miles east of Japan and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle, attacked the Japanese mainland.

“The now-famous Tokyo Raid did little real damage to Japan (wartime Premier Hideki Tojo was inspecting military bases during the raid; one B-25 came so close, Tojo could see the pilot, though the American bomber never fired a shot)—but it did hurt the Japanese government’s prestige. Believing the air raid had been launched from Midway Island, approval was given to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s plans for an attack on Midway—which would also damage Japanese “prestige.” Doolittle eventually received the Medal of Honor.

According to Wikipedia, “Following the Doolittle Raid, most of the B-25 crews who had reached China eventually achieved safety with the help of Chinese civilians and soldiers. Of the 16 planes and 80 airmen who participated in the raid, all either crash-landed, were ditched, or crashed after their crews bailed out, with the single exception of Capt. York and his crew, who landed in the Soviet Union. Despite the loss of these 15 aircraft, 69 airmen escaped capture or death, with only three killed in action. The people who helped them paid dearly for sheltering the Americans. Most of them were tortured and executed for giving aid. During the search an estimated 250,000 Chinese lives were taken by the Japanese Imperial Army. Eight Raiders were captured, but their fate was not fully known until 1946. Some of the men who crashed were aided by Patrick Cleary, the Irish Bishop of Nancheng. Japanese troops retaliated by burning down the city.

“The crews of two aircraft (10 men in total) were unaccounted for: those of 1st Lt. Dean E. Hallmark (sixth aircraft off) and 1st Lt. William G. Farrow (last aircraft off). On 15 August 1942, the United States learned from the Swiss Consulate General in Shanghai that eight of the missing crew members were prisoners of the Japanese at the city's police headquarters. Two of the missing crewmen, bombardier SSgt. William J. Dieter and flight engineer Sgt. Donald E. Fitzmaurice of Hallmark's crew, were found to have drowned when their B-25 crashed into the sea. Both of their remains were recovered after the war and were buried with military honors at Golden Gate National Cemetery.

“The other eight were captured: 1st Lt. Dean E. Hallmark, 1st Lt. William G. Farrow, 1st Lt. Robert J. Meder, 1st Lt. Chase Nielsen, 1st Lt. Robert L. Hite, 2nd Lt. George Barr, Cpl. Harold A. Spatz, and Cpl. Jacob DeShazer. All eight captured in Jiangxi were tried and sentenced to death at a military trial in China, and then transported to Tokyo. There the Army Ministry reviewed their case, with five of the sentences being commuted and the other three being executed (presumably also in Tokyo or nearby). Out of the 80 crewmen, 3 died, 8 were captured and 3 were killed in captivity by the Japanese.

“The surviving captured airmen remained in military confinement on a starvation diet, their health rapidly deteriorating. In April 1943, they were moved to Nanjing, where Meder died on 1 December 1943. The remaining men—Nielsen, Hite, Barr and DeShazer—eventually began receiving slightly better treatment and were given a copy of the Bible and a few other books. They were freed by American troops in August 1945. Four Japanese officers were tried for war crimes against the captured Doolittle Raiders, found guilty, and sentenced to hard labor, three for five years and one for nine years. Barr had been near death when liberated and remained behind in China recuperating until October, by which time he had begun to experience severe emotional problems. Untreated after transfer to Letterman Army Hospital and a military hospital in Clinton, Iowa, Barr became suicidal and was held virtually incommunicado until November, when Doolittle's personal intervention resulted in treatment that led to his recovery. DeShazer graduated from Seattle Pacific University in 1948 and returned to Japan as a missionary, where he served for over 30 years.

“Total crew casualties: 3 KIA: 2 off the coast of China, 1 in China; 8 POW: 3 executed, 1 died in captivity, 4 repatriated. In addition, seven crew members (including all five members of Lawson's crew) received injuries serious enough to require medical treatment. Of the surviving prisoners, Barr died of heart failure in 1967, Nielsen in 2007, DeShazer on 15 March 2008, and the last, Hite, died 29 March 2015.”

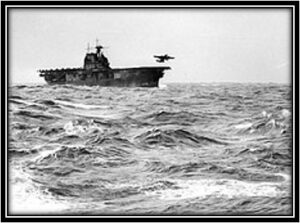

And this second of our two aviation history vignettes this day, at first blush, isn’t “aviation” in nature, but it has an aviation “edge” to it based on my recollections of personal experience. On this day in 1983, I was piloting a CH-46F “Sea Knight” helicopter launched from the USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2—like a mini aircraft carrier) and landed in the street across from the US Embassy in Beirut, Lebanon.

While doing this, I should have remembered that this was the same day, 41 years earlier, that the Doolittle Tokyo Raid had occurred. But I didn’t. I guess I was too focused on what I and my wingmen were doing, not focused on WWII history. But there was an interesting connection that would only play out years later. My co-pilot, Brian Crittendon, having received “the calling”, would go on to resign his USMC commission and become a minister, not unlike the Doolittle Raider who became a missionary.

We were having chow in the officer’s wardroom (I was assigned to the “ready crew” to launch quickly if necessary so we had already preflighted and briefed and were ready to be airborne at a moment’s notice) and we felt the ship shudder, all 18, 500 tons of it.

Helicopter pilots, perhaps more than any other kind of pilot, are very sensitive to strange noises or vibrations because of the nature of their aircraft and their design of thousands of pounds and hundreds of pieces of metal spinning around at high RPM, where just one small piece falling out of its place could spell doom. I recall we stopped eating and asked each other what the hell that weird shudder could have been.

Shortly thereafter the ship was called to general quarters, which meant we were all to immediately get to our battle stations. We rushed to our aircraft already spotted on the flight deck, got the aircraft started, and prepared to launch. Mission orders were transmitted once we were airborne.

Upon being launched from the flight deck, my section of two aircraft was directed to proceed to the US Embassy situated along the once beautiful and European-like Beirut waterfront to recover casualties from the collapsed US Embassy. I ordered my wingman to hold off-shore while I flew low over the embassy to pick out our places to land, rejoined my wingman, and came around for our approach and landing. The wide boulevard, though strewn with debris from the suicide blast, was cleared of large obstacles…mostly large pieces of the embassy’s concrete façade blown into the street…by the Marines who had arrived just minutes ahead of us to secure the area and was made large enough to land two CH-46F Sea Knight helicopters to begin the messy job of hauling dead and injured from the blast back to the USS Iwo Jima for triage medical and surgical procedures or…unfortunately…mortician services.

According to History.com, “the US embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, was almost completely destroyed by a car-bomb explosion that killed 63 people, including the suicide bomber and 17 Americans. The terrorist attack was carried out in protest of the US military presence in Lebanon.

“In 1975, a bloody civil war erupted in Lebanon, with Palestinian and leftist Muslim guerrillas battling militias of the Christian Phalange Party, the Maronite Christian community, and other groups. During the next few years, Syrian, Israeli, and United Nations interventions failed to resolve the factional fighting, and on August 20, 1982, a multinational force featuring US Marines landed in Beirut to oversee the Palestinian withdrawal from Lebanon.

“The Marines left Lebanese territory on September 10 but returned on September 29, following the massacre of Palestinian refugees by a Christian militia. The next day, the first U.S. Marine to die during the mission was killed while defusing a bomb, and on April 18, 1983, the US embassy in Beirut was bombed. On October 23, Lebanese terrorists evaded security measures and drove a truck packed with explosives into the US Marine barracks in Beirut, killing 241 U.S. military personnel. Fifty-eight French soldiers were killed almost simultaneously in a separate suicide terrorist attack. On February 7, 1984, US President Ronald Reagan announced the end of US participation in the peacekeeping force, and on February 26 the last US Marines left Beirut.”

Onward and upward!