Good Saturday morning fellow ECAHF’ers. Completing twenty-five combat missions. Most of us wouldn’t bet on those odds. But we might bet on the odds at the casinos. According to Casinofreak.com, “The average payout percentage for slot machines in Las Vegas is around 85 cents per dollar earned.”

Flying B-17’s in combat over Europe in the US Army Air Forces? The odds of surviving were low. It was one of the most dangerous combat assignments during World War II. According to the Air Force Association (AFA), “More than 50,000 Airmen lost their lives in the four years of WWII and the majority of those losses were on bomber missions over Nazi Germany in B-17s and B-24s. The average age of the crew of a B-17 Flying Fortress was less than 25, with four officers and six enlisted Airmen manning the aircraft. Their chance of survival was less than 50 percent.”

We’re blessed that our youth—those who do the fighting and the bleeding and the crying and the dying—are impervious (or so they believe) to danger, invulnerable to risk, positive about their chances, and offer toasts like, “Live fast, die young, and have a good-looking corpse.” They offer such toasts because most don’t actually believe, thankfully, they will die young.

Again, according to the AFA, “In the Fall of 1943, on one daylight mission known as ‘Black Thursday,’ during operations against German industrial capability in Schweinfurt, more than 60 B-17s were lost to enemy fighter aircraft attacks.” They died young.

Yet, one of the most famous of those iconic aircraft and crew to beat the nearly insurmountable odds was the Memphis Belle, which on June 9, 1943 flew home after completing their 25th mission.

From This Day in Aviation History, © 2018, Bryan R. Swopes. “9 June 1943: After completing 25 combat missions over Western Europe from its base at Air Force Station 121 (RAF Bassingbourne, Cambridgeshire, England), Memphis Belle, a U.S. Army Air Forces Boeing B-17F-10-BO Flying Fortress, serial number 41-24485, assigned to the 91st Bombardment Group (Heavy), 324th Bomb Squadron (Heavy), was flown home by Captain Robert K. Morgan and Captain James A. Verinis.

The daylight bombing campaign of Nazi-occupied Europe was very dangerous with high losses in both airmen and aircraft. For a bomber crew, 25 combat missions was a complete tour, and they were sent on to other assignments. Memphis Belle was only the second B-17 to survive 25 missions, so it was withdrawn from combat and sent back to the United States for a publicity tour.

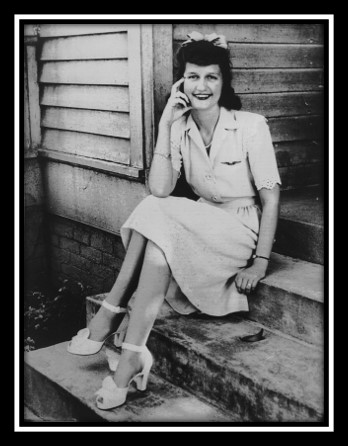

The B-17’s name was a reference to Captain Morgan’s girlfriend, Miss Margaret Polk, who lived in Memphis, Tennessee. The artwork painted on the airplane’s nose was a “Petty Girl” based on the work of pin-up artist George Petty of Esquire magazine. (Morgan named his next airplane—a B-29 Superfortress—Dauntless Dotty after his wife, Dorothy Morgan. With it, he led the first B-29 bombing mission against Tokyo, Japan, in 1944. It was also decorated with a Petty Girl.)

Memphis Belle and her crew were the subject of a 45-minute documentary, “Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress,” directed by William Wyler and released in April 1944. It was filmed in combat aboard Memphis Belle and several other B-17s. The United States Library of Congress named it for preservation as a culturally significant film.

After returning to the United States, Memphis Belle was sent on a War Bonds tour.

Following the War Bonds tour, Memphis Belle was assigned to MacDill Field, Tampa, Florida, where it was used for combat crew training.

After the war, Memphis Belle was sent to a “boneyard” at Altus, Oklahoma, to be scrapped along with hundreds of other wartime B-17s. A newspaper reporter learned of this and told Memphis’ mayor, Walter Chandler. Chandler purchased it for its scrap value and arranged for it to be put on display in the city of Memphis. For decades it suffered from time, weather and neglect. The Air Force finally took the bomber back and placed it in the permanent collection of the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, where it has been undergoing a total restoration for the last several years.

The Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress was a four-engine heavy bomber operated by a flight crew of ten. It was 74 feet, 8.90 inches long with a wingspan of 103 feet, 9.38 inches and an overall height of 19 feet, 1.00 inch. The wings have 3½° angle of incidence and 4½° dihedral. The leading edge is swept aft 8¾°. The total wing area is 1,426 square feet. The horizontal stabilizer has a span of 43 feet with 0° incidence and dihedral. Its total area, including elevators, is 331.1 square feet.

The B-17F had an approximate empty weight of 36,135 pounds, 40,437 pounds basic, and the maximum takeoff weight was 65,000 pounds.

The B-17F was powered by four air-cooled, supercharged, 1,823.129-cubic-inch-displacement Wright Cyclone G666A (R-1820-65) nine-cylinder radial engines with a compression ratio of 6.70:1. The engines were equipped with remote General Electric turbochargers capable of 24,000 rpm. The R-1820-65 was rated at 1,000 horsepower at 2,300 rpm. at sea level, and 1,200 horsepower at 2,500 rpm. for takeoff. The engine could produce 1,380 horsepower at War Emergency Power. 100-octane aviation gasoline was required. The Cyclones turned three-bladed, constant-speed, Hamilton-Standard Hydromatic propellers with a diameter of 11 feet, 7 inches though a 0.5625:1 gear reduction. The R-1820-65 engine is 3 feet, 11.59 inches long and 4 feet, 7.12 inches in diameter. It weighs 1,315 pounds.

The B-17F had a cruising speed of 200 miles per hour. The maximum speed was 299 miles per hour at 25,000 feet, though with War Emergency Power, the bomber could reach 325 miles per hour at 25,000 feet for short periods. The service ceiling was 37,500 feet.

With a normal fuel load of 1,725 gallons the B-17F had a maximum range of 3,070 miles. Two ‘Tokyo tanks’ could be installed in the bomb bay, increasing capacity by 820 gallons. Carrying a 6,000-pound bomb load, the range was 1,300 miles.

The Memphis Belle was armed with 13 Browning AN-M2 .50-caliber machine guns for defense against enemy fighters. Power turrets mounting two guns each were located at the dorsal and ventral positions. Four machine guns were mounted in the nose, 1 in the radio compartment, 2 in the waist and 2 in the tail.

The maximum bomb load of the B-17F was 20,800 pounds over very short ranges. Normally, 4,000–6,000 pounds of high-explosive bombs were carried. The internal bomb bay could be loaded with a maximum of eight 1,600-pound bombs. Two external bomb racks mounted under the wings between the fuselage and the inboard engines could carry one 4,000-pound bomb, each, though this option was rarely used.

The B-17 Flying Fortress was in production from 1936 to 1945. 12,731 B-17s were built by Boeing, Douglas Aircraft Company and Lockheed-Vega. (The manufacturer codes -BO, -DL and -VE follows the Block Number in each airplane’s type designation.) 3,405 of the total were B-17Fs, with 2,000 built by Boeing, 605 by Douglas and 500 by Lockheed-Vega.

Only three B-17F Flying Fortresses, including Memphis Belle, remain in existence. The completely restored bomber went on public display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, 17 May 2018.” © 2018, Bryan R. Swopes

Memphis Belle ® is a Registered Trademark of the United States Air Force.