Good Friday morning fellow ECAHF’ers. It’s easy to forget how many “firsts” the Soviet Space Program had. They “beat the pants” (and the skirts) off of us until all their firsts were pretty much forever buried by America’s first steps on the moon by Neil Armstrong, who coasted along to become the “toast of the town.”

While Tereshkova’s status as the first woman in space is forever secured, few in America today remember her epic journey. Perhaps in Russia they remember. But even there, I presume, her memory is eroded by subsequent spaceflight firsts by someone else. It’s a reality of human achievement and human nature that we should not be too quick to lose our humility over our own “first”, because someone is shortly about to exceed our accomplishment.

It’s a familiar story. Take the crossing of the Atlantic by air. Lindbergh was first, right? Ahh, not so fast.

The Smithsonian writes, “The U.S. Navy achieved the first transatlantic flight eight years before Charles Lindbergh became world famous for crossing the Atlantic nonstop and alone. Three Curtiss flying boats, each with a crew of six, were involved: NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4. The Navy wanted to prove the capability of the airplane as a transoceanic weapon and technology. The five-leg flight began on May 8, 1919, at the naval air station at Rockaway Beach, New York. It followed a route to Nova Scotia; Newfoundland; the Azores in the middle of the Atlantic; Lisbon, Portugal; and Plymouth, England. Only NC-4, commanded by Albert C. Read, flew the whole way. The entire trip took 24 days.”

That was big news back then…a first…and the American Navy NC-4 crew that made it all the way were heroes. Until they weren’t and their “first” was surpassed by Brits John Alcock and Arthur Brown who flew across the Atlantic non-stop with the help, according to History.com, “of a sextant, whisky, and coffee in June 1919—a month after the NC-4 flight and eight years before Charles Lindbergh’s flight”. Read more about this epic flight here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transatlantic_flight_of_Alcock_and_Brown

And while we forget Alcock and Brown, most of us also don’t know that a month later, in July 1919, the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic with paying customers was made by an RAF crew flying His Majesty's Airship R34.

Of course, there’s nuance to each of these firsts. There’s always nuance. As with Lindbergh’s flight, the first two crossings were easterly…with the prevailing winds. The R-34 was the first westerly crossing (England to Long Island in the U.S.), made more difficult because of the rigid airship’s flight against the prevailing winds. The R-32’s second “first” was turning around and flying back to Europe, thereby completing the first double crossing of the Atlantic.

Still, all those “firsts” were surpassed—at least in popular memory if not in actual achievement—by Lindbergh’s solo, non-stop flight across “the pond” in 1927. C’est la vie.

Likewise, the successful mission to “land a man on the moon and return him safely to the Earth” (words from the 1961 JFK speech) buried the many firsts of the Soviet space program, again at least in popular memory, including the June 16, 1963 space flight aboard Vostok 6 by Soviet Cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova who became the first woman in outer space.

From History.com: “After 48 orbits and 71 hours, she returned to earth, having spent more time in space than all U.S. astronauts combined to that date.

Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova was born to a peasant family in Maslennikovo, Russia, in 1937. She began work at a textile factory when she was 18, and at age 22 she made her first parachute jump under the auspices of a local aviation club. Her enthusiasm for skydiving brought her to the attention of the Soviet space program, which sought to put a woman in space in the early 1960s as a means of achieving another “space first” before the United States. As an accomplished parachutist, Tereshkova was well-equipped to handle one of the most challenging procedures of a Vostok space flight: the mandatory ejection from the capsule at about 20,000 feet during reentry. In February 1962, she was selected along with three other woman parachutists and a female pilot to begin intensive training to become a cosmonaut.

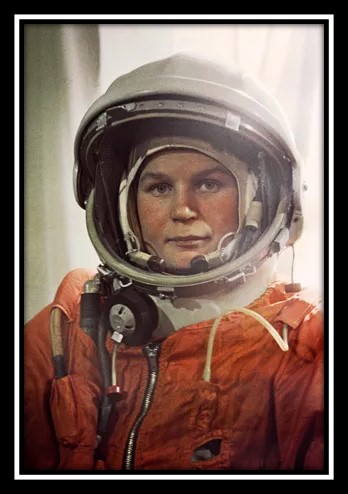

Tereshkova (courtesy Encyclopedia Brittanica)

In 1963, Tereshkova was chosen to take part in the second dual flight in the Vostok program, involving spacecrafts Vostok 5 and Vostok 6. On June 14, 1963, Vostok 5 was launched into space with cosmonaut Valeri Bykovsky aboard. With Bykovsky still orbiting the earth, Tereshkova was launched into space on June 16 aboard Vostok 6. The two spacecraft had different orbits but at one point came within three miles of each other, allowing the two cosmonauts to exchange brief communications. Tereshkova’s spacecraft was guided by an automatic control system, and she never took manual control. On June 19, after just under three days in space, Vostok 6 reentered the atmosphere, and Tereshkova successfully parachuted to earth after ejecting at 20,000 feet. Bykovsky and Vostok 5 landed safely a few hours later.

After her historic space flight, Valentina Tereshkova received the Order of Lenin and Hero of the Soviet Union awards. In November 1963, she married fellow cosmonaut Andrian Nikolayev, reportedly under pressure from Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who saw a propaganda advantage in the pairing of the two single cosmonauts. The couple made several goodwill trips abroad, had a daughter, and later separated. In 1966, Tereshkova became a member of the Supreme Soviet, the USSR’s national parliament, and she served as the Soviet representative to numerous international women’s organizations and events. She never entered space again, and hers was the last space flight by a female cosmonaut until the 1980s.

The United States screened a group of female pilots in 1959 and 1960 for possible astronaut training but later decided to restrict astronaut qualification to men. The first American woman in space was astronaut and physicist Sally Ride, who served as mission specialist on a flight of the space shuttle Challenger in 1983.”